In the previous blog, we have established that the vast majority of stones in Armenia are of igneous origin and we briefly mentioned that there are 7 volcanic sources on the current territory of Armenia. Let's have a closer look at these mountains.

There are seven active and extinct volcanos with various heights and latitudes and those are Ara, Aragats, Alages, Arteni, Gegham, Porak and Tskhouk-Karchar.

|

| The Mounts on the map of Armenia |

Mt Ara (Arayi Ler): Elevation - 2577m, Coordinates -

40°14′N 44°16′E / 40.24°N 44.27°E, last erupted - N/A

|

| Mt Ara canyon |

The mountain is called after Armenian King Ara Geghetsik. According to the legend during the war against Assyrian queen Shammuramat King Ara arranged his army at the foot of mount Ara, and the queen-on the slope of Hatis. Unfortunately the king fell in the battle and the mountain is said to be the body of Ara.

There is very little information available upon Mt Ara, including the date of last eruption, the types of rocks and minerals etc.

Mt Aragats: Elevation - 4095m, Coordinates - 40°32′N 44°12′E / 40.53°N 44.20°E, last erupted - Holocene

|

| Mt Aragats Panoramic view |

Aragats is dissected by glaciers and is of Pliocene-to-Pleistocene age, however, parasitic cones and fissures are on all sides of the volcano and were the source of large lava flows that descended its lower flanks.

Several of these were considered to be of Holocene age, but later Potassium-Argon dating indicated mid- to late-Pleistocene ages. The youngest lower-flank flows have not been precisely dated but are constrained as occurring between the end of the late-Pleistocene and 3000 BC. A 13-km-long, WSW-ENE-trending line of craters and pyroclastic cones cuts across the northern crater rim and is the source of young lava flows and lahars; the latter were considered to be characteristic of Holocene summit eruptions. The Western and Southern slopes of Mt. Aragats are home to many petroglyphs dating from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age.

Here again, there is a mythology involved in the story of the mountain. Legend holds that when Saint Gregory the Illuminator prayed one day on Mount Aragats a miraculous ever-burning lantern hanging from the heavens came down to shed light on him.

Armenians believe that the Illuminator’s lantern is still there, and only those pure in heart and spirit can see the eternal lantern — the symbol of hopes and dreams of the nation.

|

| Cones and fissures on Mt Aragats |

Mt Alages (Dar-Alages): Elevation - 3329m, Coordinates - 39°42′00″N 45°32′31″E / 39.70°N 45.542°E, last erupted - 2000 BC

|

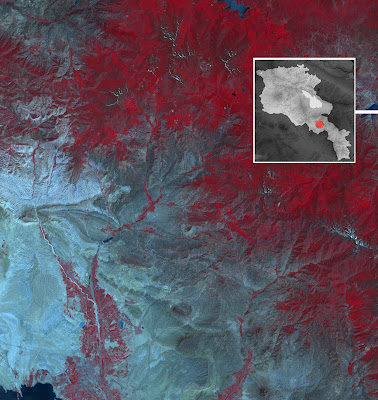

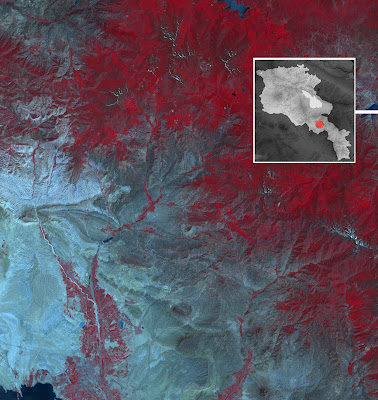

| Alages- Infrared Smithsonian description from NASA lab |

Located in southern Armenia on the western slopes of Vardenis volcanic ridge, south of Lake Sevan, Alages consists of a group of six cinder and lava cones of Pleistocene-to-Holocene age. The andesitic Dar-Alages volcano was formed in postglacial times and the last eruption occurred around 3rd millennium BC (Sviatlovsky, 1959). The Vaiyots-Sar (sar means mountain in Armenian) and Smbatassar pyroclastic cones of Holocene age (Karakhanian, 2002) are located in this part of the Vardenis volcanic ridge. Vaiyots-Sar volcano lies just north of the major Areni-Zanghezour Fault, near the town of Vaik, and used to produce a fissure-fed lava flow several thousand years ago that dammed the Arpah River down to the west for 6 km. The youthful-looking Smbatassar cinder cone is located 17 km to the North West and accumulated lava flows that travelled 11km and 17 km north and south, respectively.

Mt Arteni (Arteni Ler) : Elevation - 2047m, Coordinates - 40°22'49" N 43°48'9" E, last erupted 1340

|

| Arteni Ler |

This is perhaps the youngest of all the volcanos, with the last eruption registered at 1340 and to this date, the mountainous area is prone to destructive earthquakes (on average one every 50 years), with occurrences at >7 Richter. This means that when a strong earthquake occurs, damage will be slight in specially designed structures but considerable in ordinary substantial buildings with partial collapse.

Geghama Mountains: Elevation - 3597m, Coordinates - 40°16′30″N 44°45′00″E / 40.275°N 44.75°E, last erupted 1900 BC

|

| Gegham Ridge satellite view |

The Geghama Rindge is of volcanic origin including many extinct volcanoes. The range is70 km length and 48 km width, stretching between Lake Sevan and the Ararat plain. The highest peak of the Geghama Mountains is the Azdahak, at 3597m and the average elevation of the Geghama mountain range is near 2500m. They are formed by a volcanic field, containing a broad concentration of Pleistocene-to-Holocene lava domes and cinder cones. The volcanoes and associated lava flows cover a 65-km-long, 35-km-wide area west of Lake Sevan and south of the Hrazdan River and are concentrated along 3 NNW-SSE-trending alignments. Lava streams from the central and eastern clusters used to flow into Lake Sevan. Initial explosive eruptions at the Gegham Ridge volcanic field were followed by the extrusion of rhyolitic obsidian lava domes and flows. The latest activity produced a series of andesitic and basaltic-andesite cinder cones and lava flows. The central and eastern portions of the Gegham Ridge contains large areas of Holocene eruptions with morphologically fresh lava flows devoid of vegetation.

A great number of petroglyphs (rock-carvings) has been found in the area of Geghama Mountains dating back to around 7000 and 9000 BCE. Most images depict men in scenes of hunting and fighting, and astronomical bodies and phenomena: the Sun, the Moon, constellations, the stellar sky, lightning, etc.

|

| Petroglyph rock from Ughtasar, 9000-7000 BCE |

Mt Porak: Elevation - 2800m, Coordinates - 40°01′N 45°47′E / 40.02°N 45.78°E, last erupted 773 BC

|

| Air photo of Holocene lava flows of the Porak |

Porak is a mid-Pleistocene stratovolcano located in the Vardenis volcanic ridge about 20 km SE of Lake Sevan at the border of Armenia and Azerbaijan, hence the lava flows extend into both countries. The flanks of the volcano are dotted with 10 satellite cones and fissure vents. Porak volcano was constructed along the active Pambak-Sevan strike-slip fault, which has bisected the mid-Pleistocene Khonarassar volcano, separating its two halves by about 800 m. Two large lava flows from Porak volcano travelled up to 21 km North and North West, and fresh-looking lava flows form peninsulas extending into Lake Alagyol. Fifth century BC petroglyphs were interpreted to depict volcanic eruptions (Karakhanian et al., 2002). Porak volcano is referred to in a famous cuneiform inscription as Mount Bamni, and stratigraphic and archaeological evidence indicates that an explosive eruption also producing a lava flow occurred at the time of a military battle dated to 782-773 BC.

Mt Tskhouk-Karchar: Elevation - 3000m, Coordinates - 39°44′N 46°01′E / 39.73°N 46.02°E, last erupted 3000 BC

|

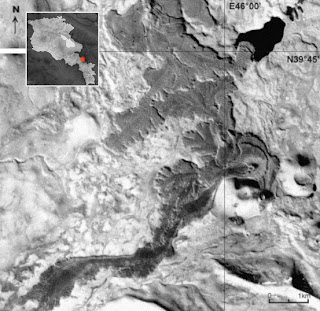

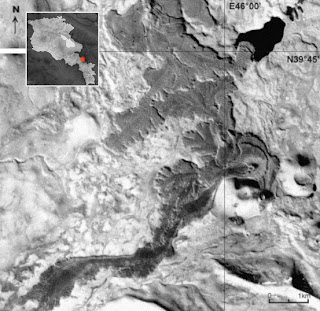

| Air photo of lava flows for the Tskhouk–Karckar |

A group of pyroclastic cones is located in the central part of the Syunik volcanic ridge along the Armenia/Azerbaijan border about 60 km south east of Lake Sevan. The Tskhouk-Karckar volcano group was constructed within offset segments of the major Pambak-Sevan strike-slip fault trending SE from Lake Sevan. Eight pyroclastic cones produced three generations of Holocene lava flows (Karakhanian et al., 2002). Abundant petroglyphs, burial kurgans, and masonry walls were found on flows of the older two age groups, but not on the youngest. Lava flows from cinder cones of the Tskhouk-Karckar volcano group overlie petroglyphs dated to the end of the 4th millennium and beginning of the 3rd millennium BC and are themselves used in gravesites dated at around 2720 BC. Following these eruptions, the area was not repopulated until the middle Ages.